Smugglers, Bootleggers, And Scofflaws:

Prohibition And New York City

By Ellen NicKenzie Lawson PH.D.

Tag Cloud

Prohibition on Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket

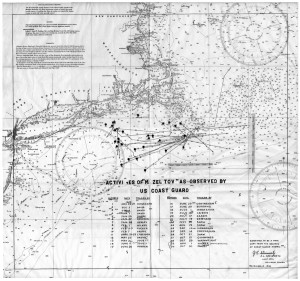

Nautical Chart showing various locations of Mazel Tov on Rum Row according to Coast Guard

Prohibition on Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket

by Ellen NicKenzie Lawson c. 2016

Liquor smuggling was common during Prohibition in the waters around Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket. Rum Row, the floating liquor “store” of foreign and domestic boats, was located just 12 miles southeast of Nantucket.

Nomansland, south of the Vineyard, was used as storage for liquor from the Row during winter.

Piracy was a problem in the early days when the Coast Guard lacked manpower and ships (from the Navy) to patrol the waters effectively. A notorious piracy between Cuttyhunk and the Vineyard occured one foggy day in 1923. Soon, barrels of beer and the bodies of seven dead men in life preservers floated in Vineyard Sound. A dory containing another dead man beached itself at Menemsha. It was never clear exactly what happened. Authorities believed a New York City liquor cartel had hijacked the ship of another cartel and murdered its crew.

After 1924, the Coast Guard had adequate manpower and ships. Then Rum Row was closely monitored. This included following foreign ships, sometimes for an entire year, to prevent their making contact with American ones. The Mazel Tov was dogged in this way, its trail picked up each time it returned to Rum Row. When it strayed half a mile within the 12 mile limit, south of Martha’s Vineyard, the ship was seized.

But the international treaty of 1924 had established a new legal limit which extended it from three miles to twelve miles out, although the limit was actually defined as “one hour” from shore. The owners, the Bronfman family of Canada, later proved in court their ship could go no faster than ten miles an hour. So the ship was released.

Two syndicates vied for control of liquor landed on Nantucket. Most of it was bound for Boston or New Bedford. Both gangs had short-wave radio stations on the island to contact Rum Row.

One of these gangs harassed bathers on Siasconset Beach because a landing of liquor was coming ashore there. So the gangsters ran around like zombies, knocking over beach umbrellas, cursing, and yelling at innocent people sunning and swimming.

When the New York Yacht Club’s Annual Regatta finished at Nantucket, a small scruffy-looking boat anchored in Nantucket harbor aroused suspicions of the authorities. This was because its crew was not dressed in typical yachting whites, and the crew was going around the harbor taking orders for liquor.

A fishing vessel sighted off the fishing grounds south of the Vineyard was seen earlier on Rum Row. So the boat was stopped and searched. Four fish were found placed casually on tops of hundreds of cases of liquor.

Another time a sword-fishing schooner, aground off Squibnocket Point, was abandoned. Locals claimed this particular schooner had neither owner nor guests aboard. All the islanders assumed the schooner was actually a rumrunner.

Another time a sword-fishing schooner was sighted in Edgartown with machine guns mounted on deck.

When a fishing boat from New Bedford went aground in the fog near Chilmark, its captain did not call for help. Even though the Coast Guard was nearby Woods Hole. Instead, the captain went ashore and phoned for a private tug. But a beachcomber, seeing the wreck, did call the Coast Guard. When the captain refused its help, this aroused suspicions. So guardsmen went aboard the listing ship with six-foot probes. They found liquor cases below the fish. When ocean swells broke open the hatch, hundreds of cases of liquor washed overboard even as guardsmen, waist deep in freezing water in the hold, saved 200 cases as evidence.

News that cases of free liquor were floating up on Vineyard beaches spread quickly. Islanders arrived to salvage the cases. For weeks, bottles broke up on shore. The smell of liquor lingered over the beach. Successful salvagers reported that the liquor was inferior. Was this to discourage rival salvagers?

Rumrunners insisted on having the fastest boats available. These were tested before purchase. The Coast Guard seized one of these boats making a test run off Gay Head. The case was throw out of court because no liquor was aboard.

During chases, smugglers would fire at fellow smugglers but tried not to return fire at the Coast Guard. Instead they would speed away to deliver the goods. One hand-drawn map in the National Archives documents gunfire by the Coast Guard at smugglers off the Vineyard’s East Chop and West Chop.

One of the best known early smugglers was Captain Bill McCoy. He kept an eye on his ships on Rum Row while hiding on shore near Gay Head among the Wampanoag, whom he trusted not to reveal his whereabouts. McCoy’s liquor was good quality, not watered down. The “the real McCoy,” is attributed to him, referring to his good liquor.

[See also Smugglers, Bootleggers, and Scofflaws: Prohibition and New York City (SUNY Pres, 2013) by Ellen NicKenzie Lawson, available in paperback and as an e-book. It is a scholarly book, less than 200 pages, with text, photos, primary documents, extensive footnotes, and index. Lawson’s research also appeared as an article in Nantucket Life c. 2004.

For more details behind this essay, click on “Alphabetical list of rum runners for Cape and Islands,” also on this web site. Names of ships, locations of seizure, and dates are given there. Lawson’s research notes for the Cape and Islands, using 90 boxes of Coast Guard records for the Prohibition era, are housed at the Nickerson Library at Cape Cod Community College.]